Sometimes in American history, immigrants deeply influence a place and its people not by fitting in, but by standing apart.

One such story involves a cultured Parisian family that found its way to Kentucky.

The story starts in 1790. Though France was not a leading source of immigration to the young United States, that year some 500 French citizens managed to found the town of Gallipolis in southeast Ohio, then the Northwest Territory.

These settlers were not aristocrats fleeing for their lives but merchants and craftsmen whose clientele had emigrated at the outbreak of the French Revolution. They were surprised by what they found: America was not the Eden that smooth-talking salesmen had told them about, nor did they hold the land titles they thought they had paid for.

Young Waldemar Mantelle was a late arrival among these Ohio Frenchmen. He had no claim to land but found work as a scout, hiking through the woods every day to look for signs of Indian presence.

Mentelle left France because of the Revolution, but his was a reluctant departure. In late 1789, before the Terror, his father worried his son might be conscripted and so bought his passage to America. He also thought that Waldemar, who showed no interest in pursuing a profession, had no prospects for making a living in France. In the New World, land was cheap and abundant and Waldemar could take up farming, his father decided.

Mentelle spent a year in New York and Philadelphia looking for work before hitching a ride with General St. Clair’s flatboats carrying troops down the Ohio en route to the Battle of the Wabash. The battle turned out to be the largest victory ever won by American Indians, and the worst defeat in U.S. military history.

Fortunately for Mentelle, he disembarked at Gallipolis. There, he pined for the woman he left behind in France: Charlotte LeClerc, the daughter of an army doctor who raised her to withstand any hardship, making her swim the Seine before breakfast, locking her in a closet with the corpse of an acquaintance, and teaching her to ride and shoot.

A historic marker showing Mentelle Park. Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Runyon.

But LeClerc set sail to find Mantelle by herself. In April 1794, she arrived in Gallipolis, armed with the blunderbuss her father had given her. She may have needed it to ward off capture by the sans-culottes, for by then leaving France was a crime punishable by death.

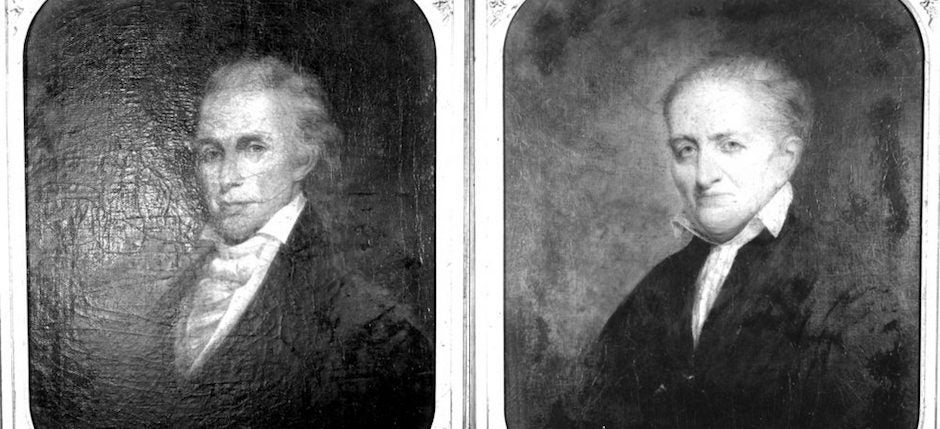

Mentelle and LeClerc married immediately and began producing a family of eight children. In addition, they produced many vivid letters, which have only recently come to light.

Gallipolis was not to Charlotte’s taste, and they left for Kentucky as soon as Waldemar could complete his scouting assignment. Years later, however, they looked back on those frontier days as the best time of their lives, she because of deep friendships formed, he because of the free living “with only the bare necessities, no ambition and no concern for the future.”

In Kentucky, they settled in the village of Washington, where they raised and sold produce for a couple of years, before relocating south to Lexington in 1798. Lexington was a larger and more cultured place where they hoped to make a living as teachers of French and dancing. When that did not succeed, they returned to farming on rented land just outside the city.

As the years went by, Waldemar plied many trades, including house painter, horse veterinarian, potter, silhouette artist, land agent for Pierre Samuel du Pont, and commission merchant, selling such “curious, elegant, and useful articles” as linen, china, brandy, whiskey, figs, raisins, almonds, oysters, mackerel, patent medicines, snuff, jewelry, mirrors, fiddles, and toys.

In 1817 their friend and neighbor Henry Clay found him a job at the local branch of the Second United States Bank, relieving him of the ups and downs of commercial life.

In 1820 Charlotte began the teaching career for which she would be most remembered. She founded Mentelle’s for Young Ladies, an intellectually rigorous and fashionable school with classes taught in French.

Her most famous student, a star actress in the school’s theatrical productions, was Mary Todd. The future Mrs. Abraham Lincoln lived with the Mentelles from 1832 to 1836, preferring Madame Mentelle to her disagreeable stepmother. “My early home was truly at a boarding school,” she later told her White House seamstress.

Despite these outward signs of success, the Mentelles were never financially secure. “We always have the devil by the tail,” Charlotte wrote a friend in 1827, “and we’re just grateful when it doesn’t break off in our hand. The French do not strike it rich in this country. Though that was never my ambition, I do not like always having to be on the point of becoming poor.”

She also complained that there were all too many woods, and that the local people lacked the sophistication needed to connect with a “sensitive Frenchman.” The place was primitive, she wrote in April 1804: “There is no society. The nature of the people and their mores are against it. They have crude vices and no attractive virtues.”

The Mentelles became Americans on their own terms, unrepentantly French to the end.

Waldemar held similar views, telling du Pont de Nemours that a pleasant existence can be had if one has the money to buy enslaved persons, but only on condition of being “willing to forget that there is no society here at all, no opening of the heart, that our children will maybe turn into unhappy savages and learn to despise their parents.”

Charlotte brought up that topic as well, writing that although the American form of government “can be taken as a model,. this Constitution that speaks only of liberty; these men who seem to think nobly—if you compare all that with slavery and their tyranny over the blacks,” it is “ridiculous and absurd.” She continued that if you should happen to mention this inconsistency to the people here, “they become disturbed, and you would think you were listening to madmen who believe they are speaking rationally.”

Being French in America, in Waldemar’s estimation, meant being at a distinct disadvantage in any commercial transaction. “Not one of our compatriots has prospered. He is cheated without mercy,” he wrote. He told du Pont de Nemours of a French Kentuckian who had paid for the same property four or five times and after 10 years of trying still could not prove ownership. Another was continually “vexed and tormented . . . . ”

Waldemar lamented that, “Here one has to be a charlatan or a Presbyterian—more or less the same thing—to succeed.”

He described the typical Kentuckian as “Adroit, cunning, and a knave, whose god is money. He knows no other except when he goes to a church to exchange this passion during an hour or two for the most stupid fanaticism.”

Products of the French Enlightenment, the Mentelles shocked their neighbors by their lack of religiosity. Amos Kendall wrote in his journal in 1814, “I was obliged to listen to a long talk in ridicule of religion and religious men. The parties concerned were Mr. and Mrs. Mentelle, professed deists.”

Yet the Mentelles found their nationality was an advantage in certain social situations. Lexington’s elite thought having the Mentelles in their midst gave them a touch of class. The French couple was invited to mingle with the rich and prominent without being expected to return the favor, which they did not have the money to do. Charlotte saw that they were too poor to incite envy yet were perceived as better educated than their hosts, eliciting from the latter “a bit of the esteem that they normally only have for gold.”

Charlotte was a feminist before her time—a woman of strong opinions who saw through the pretenses of slave-owning Christians and corrupt politicians. In translating a pamphlet about the French Revolution in 1799 she inserted her own comments about the injustices women have suffered through the ages and the power they nevertheless wield behind the scenes. She cut her hair short and dressed like a man, and scandalized her neighbors by walking miles a day through the streets of Lexington all while reading a book.

The Mentelles became Americans on their own terms, unrepentantly French to the end. Now they are memoralized as iconic Kentuckians; Lexington has a street and a new historical marker to remember them by.

Randolph Paul Runyon, professor emeritus at Miami University of Ohio, is the author of The Mentelles: Mary Todd Lincoln, Henry Clay, and the Immigrant Family Who Educated Antebellum Kentucky

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli | Secondary Editor: Joe Mathews

Add a Comment