For Refugee Children in Baltimore and Their Teacher, Art Is a Safe Zone

Picturing a Home Away From Home That Is Free and Secure

Students in a Baltimore program for refugee youth made models of their personal sanctuaries. Rana, from Iraq, built a house. "A sanctuary represents peace," she wrote.. "The coolest part of my sanctuary is the four seasons." Photo by Ben Hamburger.

I am an artist and educator pursuing an MFA in Community Arts at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Last year, as part of my Master’s studies, I began teaching art to young refugees. The students were participants in the Baltimore City Community College Refugee Youth Project (RYP), a grant-funded organization that provides after-school programming for relocated kids. They were just a few of the thousands of refugees who had resettled in Maryland in recent years, and they had endured hardships I could hardly imagine. The kids and their families had fled troubles in Nepal, Myanmar, Eritrea, South Sudan, and Iraq. Now they were going to face another set of difficult challenges acclimating to American life. My arts curriculum would give them an opportunity to tell their stories and have some fun, while helping them adjust as smoothly as possible.

I decided to build the class around the idea of sanctuary, and to have the kids depict their safe places through art. I wanted to distinguish sanctuary as a special zone, where they would be free and safe to be who they want to be, no matter what. I wanted our class to be a springboard to help the students create sanctuary in the world outside our class. I hoped my students would collectively envision an America where all of their sanctuaries would exist, together, in peace. What I didn’t expect was that the kids would teach me so much about my own American sanctuary. Through them, I realized that the America that makes me proud depends on the ability of people other than me to create homes and thrive culturally, strengthening communities.

Courtesy of Ben Hamburger.

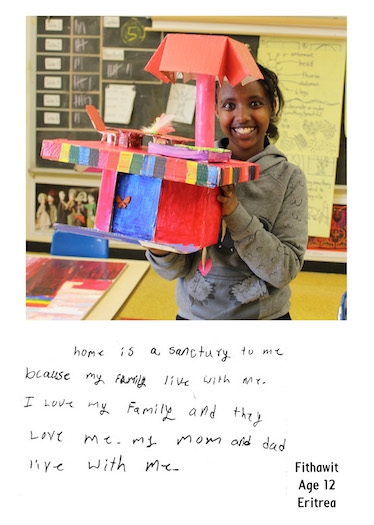

I worked with two groups: a small group of teenagers from Myanmar, and a class of seventeen elementary schoolers from the other countries. The first group of students was contemplative, took great care with their artwork, and wore a thin cloak of teenage angst. The younger kids were a rambunctious ball of energy and emotion. Rana, from Iraq, was sensitive and always eager to express her feelings through drawing. One day, frustrated after being bullied during the school day, she embellished a previously-completed pencil sketch of her sanctuary—a house—with ferocious lightning bolts. Fithawit, a 12-year-old from Eritrea, assumed a leadership role in the class, earning access to the materials closet and helping the younger kids.

It was no coincidence that the students ended up in Baltimore. Waves of immigration and industry once made Baltimore a thriving port-town, with a population topping out around 950,000 in 1950. But since then, the city, like so many struggling industrial centers, has lost about one-third of its people. Former mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake sought to rebuild in part by increasing the number of refugee families resettled here. Today, in addition to established, culturally rich neighborhoods like Greektown, Little Italy, and Highlandtown (the flourishing Latino hub where I live), Baltimore is becoming home to Nepali, Burmese, Sudanese, Eritrean, and Middle Eastern enclaves.

Rana, Fithawit and the others had arrived in a place that would welcome them, but I worried about triggering traumatic memories. So in class, at first, we didn’t talk of wars or government. We made a bird and tree sanctuary. Crafting colorful creatures and plants with oil pastels and water colors, the kids conjured a place where their birds and trees could grow and enjoy productive lives without facing danger from hunters, lumberjacks, or developers. Nishan, from Nepal, drew a majestic bird with intricately drawn feathers. We eventually used it in a collage, swooping over Fithawit’s spiraling tree. In our sanctuary, the children’s bird families thrived, and their trees grew tall and strong.

Courtesy of Ben Hamburger.

We decided people might benefit from sanctuaries too. The students began to define what sanctuary meant to them. We listed elements that make homes safe, fun, and free. “You should need a password to get in,” one boy said. “It should be able to fly,” another thought. “Your whole family should live there too,” a girl mentioned. We talked about the things that made us who we are: our languages, our hobbies, the food we eat, our personalities, and our values. The students chose colors, shapes, and patterns that spoke for their personalities and cultures, and designed symbols to represent their identities. Two inseparable Eritrean girls drew beautiful multicolored floral patterns. A Burmese teenager drew a cross, representing her faith.

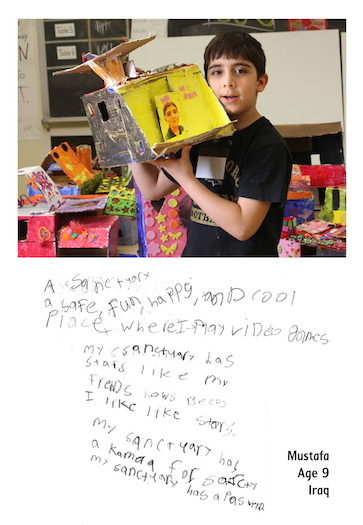

Our art room was often boisterous, a frenzy of cardboard and glue and glitter and bright-colored paint. Neither the kids’ artwork nor their behavior reflected the trauma that they had endured. They were generally happy. Gradually, they opened up and started telling me about their experiences prior to coming to Baltimore —things they missed about their home countries and cultures, as well as violence they had witnessed, separation from family members, and the grim circumstances of living in refugee camps. They began to contextualize past experiences as “not sanctuaries.” Mustafa, one of the Iraqi boys, told me about men with big guns who entered his home, and about kids without parents being forced to work and fight. Those people needed sanctuaries, too, we agreed.

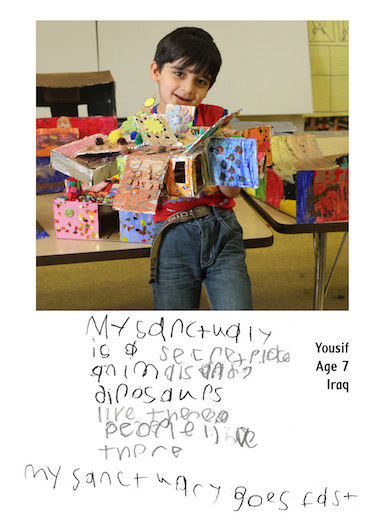

Our final project was building our own sanctuaries out of cardboard, tape, and glue, and covering them with elements that represent who we are and who we aspire to be. Mustafa’s sculpture was bright yellow and had a roof deck and swing. Fithawit’s younger sister Zebib built a sanctuary bedazzled with gemstones and glitter, with pink walls with plenty of windows. Yousif’s was equipped with wings so that it could, indeed, fly. When I put the sculptures together on tables, they transformed into an alluring colorful town. Each structure was a monument to the artist that created it, but together they built a neighborhood. Mayor Rawlings-Blake invited us to exhibit our work in a gallery in Baltimore City Hall, hosting an opening reception where refugee families and friends joined City Hall employees and politicians to celebrate the students — affirming that their unique voices are cherished in a country that celebrates its diversity. The kids had a blast, smiling ear to ear as they ran up to guests to tell them about their work.

Courtesy of Ben Hamburger.

Art, I have found, has the unique capacity to bridge barriers. Together, my students and I developed a deeper understanding of what it means to be American—and I gained a new perspective on my own sense of ownership and responsibility to the American ideals that resonate with me. As a white man born in the United States, my sense of belonging, shelter, family, and freedom to think and act have never been at risk. I knew vaguely that I felt at peace when I wandered, at home and abroad, spending time in communities filled with colorful languages, smells, tastes, and traditions.

Looking at the kids’ sanctuaries on display at City Hall, I realized that sanctuaries are ultimately personal, but can come together to form a community greater than the sum of its parts. I would have loved strolling through the neighborhood my students created with their art. The real-life sanctuaries my students will build here in America, I now understand, are what make America a sanctuary for me.

Ben Hamburger is an artist and educator in Baltimore. He’s pursuing a Master of Fine Arts degree in Community Arts at the Maryland Institute College of Art, with a focus on painting and social change within cultural landscapes. The Refugee Youth Project is at www.refugeeyouthproject.org.

This essay is part of a Zócalo Inquiry, Do Sanctuaries Really Bring Peace?

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment