Driving north on Route 95 through Connecticut, I noticed a billboard advertising a local diner. Its immense letters spelled out: “Vegan, Vegetarian, Gluten-Free and Diner Classics.” I knew a seismic shift had occurred when Blue Plate Specials—hands-down favorites for nearly a century such as meat loaf, hot turkey sandwiches, and spaghetti and meatballs—were last on a list of diner offerings.

Over their long history, diners have been a subtle part of our built environment and also our inner landscapes. They are as familiar as the language we speak and the comfort food we eat. Everyone loves diners.

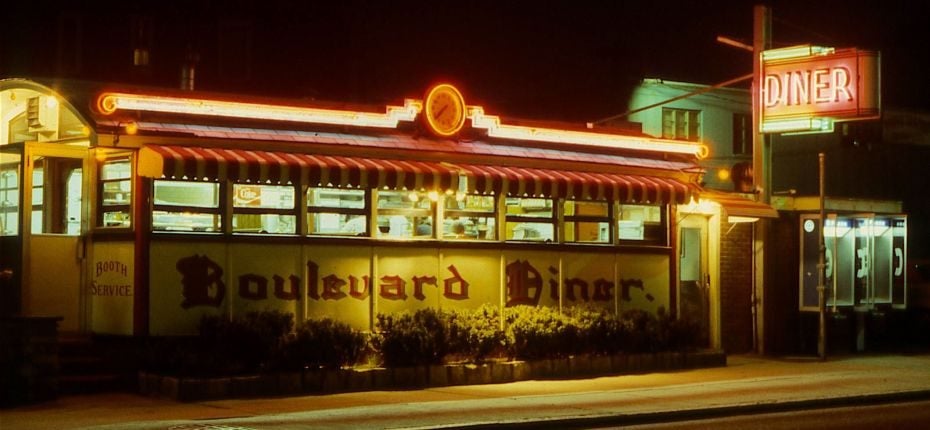

There really is no other building like a classic diner: long and low, sheathed in glass, gleaming stainless steel, and colorful porcelain enamel; often ringed in neon and punctuated by a flashy, sometimes flashing, sign; going and glowing at all hours, day and night.

The first diners showed up 135 years ago when Walter Scott served affordable fast food out of his horse-drawn wagon in Providence, Rhode Island. Patrons stood on the street to eat their lunches in the same manner as the customers of today’s ubiquitous food trucks. These eateries were constructed by wagon builders; gradually a specialized industry developed to mass produce diners.

These classic diners were factory-built, from the 1920s onward, and thus conformed to regular dimensions and proportions in order to be moved—by rail, barge, and truck—from where they were manufactured to where they would operate. As a result, diners have a generic similarity to one another. But, because they are mostly individually owned, and made by different manufacturers, they have distinct personalities, based upon the people on both sides of the counter.

The diner interior is all business, where form follows function—“as utilitarian as a machinist’s bench.” The customer can see the short order cook reach into the icebox, work the griddle, and deliver the food in an astonishingly short amount of time. The back bar of the diner, beneath the glass-fronted changeable letter menu boards, is a tour-de-force of stainless steel or colorful tile, with a line of work stations filled with grills, steam tables, sandwich boards, coffee urns, multi-mixers, drink dispensers, and display cases.

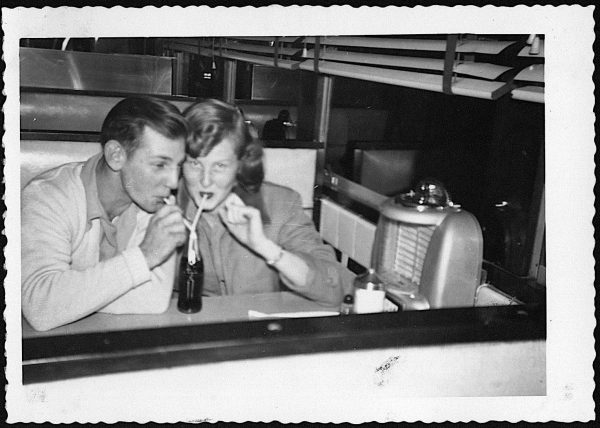

From 1955 to 1957 waitress Joan Hepner Wentzell constantly snapped photos of customers at the Pole Tavern Diner on Route 40 in Salem County, New Jersey. These sweethearts sharing a Coke remain anonymous. Photo courtesy of Richard J. S. Gutman.

The “counter culture” inside diners is a reflection of their wide appeal. Commentators have long fixated on this, describing how this spirit manifests itself.

A 1932 article in World’s Work depicted the all-inclusive range of patrons:

“The lunch wagon is the most democratic, and therefore the most American of all eating places. Actors, milkmen, chauffeurs, debutantes, nymphes du pave, young men-about-town, teamsters, students, streetcar motormen, messenger boys, policemen, white wings, businessmen—all these and more rub elbows at its counter.”

Five years later, there was a one-page story in The Literary Digest:

“If you joined diner devotees at a quick ‘cup o’ java,’ you’d find, if it were daytime, that you were rubbing shoulders mostly with horny-handed men in denim. If it were before dawn, you might be rubbing shoulders with men in tails, homeward bound from a night of revelry.” (I love the fact that in 1937 there were people described as “diner devotees.”)

Just as important as the diners’ look and feel is their chow: Always affordable, it has continuously adapted to fit the public’s desires. The norm is home-style cooking, breakfast anytime, and food that is real, local, and sustainable.

C. Oakley Ells in 1932 supplied his diner in Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, with fresh eggs, milk, and vegetables from his own Ells’ Sunnyside Farms, a stone’s throw down the road. In 2017, Champ’s Diner, in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, identifies on their menu the name of the local farm that provides their eggs.

In San Diego, California, Ray and Herb Boggs operated the Airway Diner. Their July 1942 menu included an avocado cocktail appetizer (35 cents), a natural since San Diego County was the source of most avocados in the country. You wouldn’t find that on a diner on the East Coast at that time. The seafood of the day was grilled Catalina swordfish (85 cents), caught off nearby Santa Catalina Island.

Today the Silver Diner is a locally owned and operated chain of 14 units that set out in 1989 to create a diner for the 21st century. They have continually tweaked their offerings to serve the food that people want to eat. In 2006, Silver Diner was the first chain in the Washington, D.C. area to completely remove trans fats from their menus. Now they feature local farms that supply all-natural, antibiotic- and hormone-free meats and provide non-GMO produce in season.

I’ve studied the world of diners for more than 45 years, beginning when these classic stainless-steel eateries were believed to be a dying breed. But, to paraphrase the supposed Mark Twain quote: “The report of their demise is premature.”

Every year there are articles and TV news magazine stories that proclaim either the death or the rebirth of the diner. I admit I once believed that diners might go extinct. One of my earliest articles was “Diners are declining, but great ones remain,” published in The Boston Globe, in 1974. Truth be told, more than half of the diners I profiled in that story have been demolished.

[Diners] are as familiar as the language we speak and the comfort food we eat. Everyone loves diners.

But the other half have survived. What accounts for their longevity?

In 1975, the National Trust for Historic Preservation included a session on diners and gas stations in its yearly meeting. The Christian Science Monitor noted the tension in the discussion with “Roadside architecture: is it treasure or trash?”

By the 1980s, the Henry Ford Museum, in Dearborn, Michigan, was restoring Lamy’s Diner, a 1946 streamliner, built by the Worcester Lunch Car Company. This became the first of many diners to be installed as icons of our culture in museums. Also notable, vintage diners were resurrected, and new old-style diners—like the Silver Diner—began a comeback.

This was largely fueled by Baby Boomers seeking the comfort and nostalgia of their youth. The diner was put on a pedestal as an exemplar of what’s good about America: mom-and-pop businesses; fresh, home-style food at a good value; and an individual experience that contrasted with the cookie-cutter fast food chains.

Now, the diner is clearly safe and here to stay. With great regularity, my Facebook feed will advise me of “The 21 Best Diners in America,” according to the Huffington Post; “The Top 12 New England Diners,” says Boston magazine; “13 Picture-Perfect LA Diners You’ve Never Heard Of,” proclaims EaterLA.com (and of which, I might add, none are actual diners); and “These Are the Cutest Diners In Every State,” in the eyes of Country Living.

Social media keeps diners in the headlines, in our stream of consciousness, and constantly reminds us why we love these places. There’s a magical something in that word that conjures up a place where you feel at home, can have a great meal for a good price, and walk away satisfied and with a smile on your face.

The diner of the future will continue to change subtly and dramatically simultaneously: an American trait that makes it “feel the same” while ever accommodating the evolving tastes of its customers.

Richard J. S. Gutman is the foremost authority on the history and architecture of the diner. He has written three books on the subject.

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment