In a room filled with wreaths bearing Chinese characters on broad ribbons, two Buddhist nuns in embroidered yellow robes started chanting and striking bells. One by one, members of my family, each with a black band tied around an arm, approached my grandmother’s casket. Each of us held a smoldering joss stick between prayer hands and bowed three times in respect.

We approached the casket in order of age and gender (men first): my grandfather, my Uncle Charles, my Uncle Eddy, my Aunt Alice, me (representing my mom), and my cousin, Anne (representing my Aunt Yi). We each pulled a differently colored blanket over my grandmother’s body, covering her in a kind of rainbow. To give her resources in the afterlife, we fed a fire with orange squares of paper painted with gold leaf and sheets of “Hell Bank” money. Then, led by my Uncle Charles, who held a white flag with the character for peace painted on it, my family walked solemnly in a procession around the chapel-like room.

I didn’t know what to expect when I heard that my grandmother’s funeral would be held at the Ashley & McMullen funeral home in San Francisco’s Richmond District, but it certainly wasn’t this.

The Richmond District has a rich Irish history. Ashley & McMullen is just a few blocks from the Irish Immigration and Pastoral Center, and not far from the pubs Ireland’s 32 and the Blarney Stone. But Richmond also has a large Chinese population and has long been known as San Francisco’s second Chinatown (the first is the older one downtown). So perhaps I should have known that a place with a quintessentially Irish name would be capable of executing a well-oiled, highly ritualized Buddhist funeral service. I have some Irishmen to thank for bringing me closer to my Chinese roots.

I grew up in the New Jersey suburbs outside of Philadelphia. For most of my life, my grandparents were disembodied voices calling from San Francisco. These conversations were usually comical because my grandfather, grandmother, and I were all speaking Mandarin as a second language. His native dialect was Cantonese and hers was Sichuanese, so they spoke Mandarin with heavy—and different—accents. As for me, my Chinese vocabulary was pretty thin—even though my parents spoke Mandarin at home (to which I often responded in English) and sent me to a Saturday morning Chinese school (which I hated because it prevented me from watching the cartoons my soccer team friends were always talking about).

At 5, I did spend a whole summer with my grandparents in San Francisco’s Chinatown. For much of those two months, I felt completely at sea since I couldn’t explain exactly what I wanted—and I knew I was supposed to treat them with deferential respect. I let my grandfather heat me up a Celeste pizza for lunch every day, since he assumed I wanted to eat like an American. It wasn’t until my mom came to get me at the end of the summer—and was about to tuck into a shredded pork stir fry at lunch—that I spoke up about actually wanting to eat Chinese food.

My main impression from that summer was my grandmother’s devotion to Buddhism. I remember an altar that included a bowl of oranges, a ceramic bowl filled with rice that held up joss sticks, and a rendering of a goddess in red, pink, and blue. Every afternoon, my grandfather told me to turn off the TV for about an hour so my grandmother could pace around the room, chanting and thumbing sandalwood Buddhist prayer beads.

In my mid-20s, I spent a year living in San Francisco. About once a month, I drove over to my grandparents’ apartment and helped them into my car for a trip to Lichee Garden for dim sum. My grandfather ordered soft things, like steamed sponge cake, because my grandma’s teeth ached.

Food and pictures were the lubricants of our conversations. I would bring photos of the stone city walls of Oxford, England, where I had recently finished grad school, and of my friends and me hiking through redwood forests, and explain the best I could in Mandarin. They would nod and smile, asking where my friends were from. My grandfather would send me back to my apartment with dozens of steamed cha shao (barbecue pork) and dao sa (red bean paste) buns.

When my grandma passed away on March 10, 2005, I was living in Los Angeles. I called the airline to book a special bereavement fare and was asked a few questions to confirm that I was actually going to a bona fide funeral. One of them threw me for a loop: “What is your grandmother’s name?”

In all of the years I had known her, I had always addressed her by the Mandarin words for grandmother: wai po. Her death—and the fact that I didn’t even know her name—prompted me to start asking questions.

My grandmother, Lee Yun Shu, was born on May 16, 1916, in Sichuan province’s Anyue County. She was the youngest daughter in a well-off family with a large property where tenant farmers grew rice and wheat. My great-grandfather was mayor of a subdivision near the city of Chengdu. My grandmother graduated from high school, which was unusual for local girls at the time. She could recite poems from the Tang and Song dynasties and sing songs from Chinese operas.

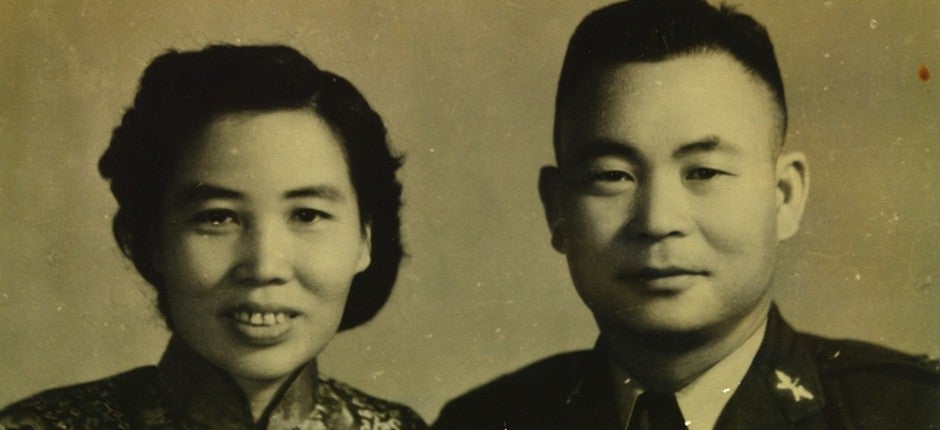

She met my grandfather, Huang Choi Kwei, in the late 1930s when he was a pilot in the air force of Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalist government, which had largely retreated into the mountainous areas of Chongqing and Sichuan during the struggle against the Japanese. Before the Japanese invasion, my grandfather was an elementary school music teacher in Guangdong province. One of his best friends married one of my grandmother’s best friends. My grandfather pursued my grandmother, even though they spoke different Chinese dialects. My grandmother’s father disowned her for marrying below her station, my mom said.

Like many mainlanders, my grandparents escaped to Taiwan when the Communists took over in 1949. Settling in the city of Tainan with five children, they barely scraped by. A government truck regularly visited the building where they lived to distribute rations of cooking oil and rice to military families, but the portions didn’t go nearly far enough. No wonder my grandmother’s Buddhist altar featured Guanyin, the goddess of mercy, who was supposed to comfort the suffering. And no wonder my grandfather felt his first duty was to make sure I never left their apartment hungry.

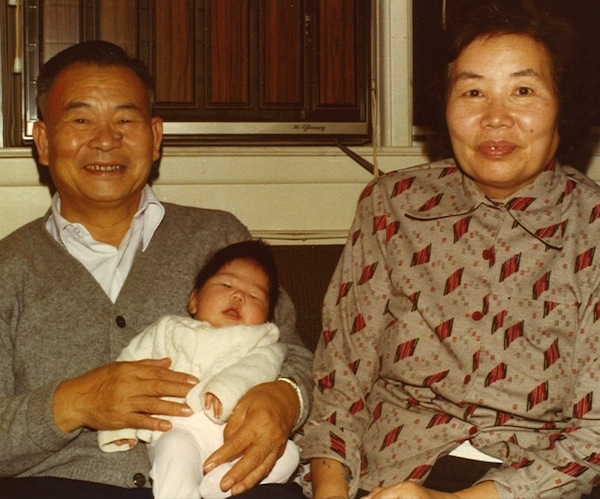

My grandparents followed my mom across the Pacific in 1977—partly because they gave her most of their retirement savings when she came to the U.S. in 1968 and because they never felt completely at home in Taiwan. By then, their other children lived in America and Canada. The siblings took turns hosting their parents.

When they lived with us in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, during the first two years of my life, my grandfather hated sitting still. He made a little extra money by picking up part-time work in Philadelphia’s Chinatown. He helped a restaurant pastry chef make dim sum treats like egg tarts and steamed buns, which explains why the buns he sent me home with as an adult were so delicious.

But for the most part, my grandparents, who were in their 60s when they arrived, found it difficult to get used to this country. The family found a high-rise apartment building in San Francisco’s Chinatown for fixed-income seniors, and my grandparents moved into a rental unit in the mid-1980s. They learned enough English to pass the U.S. citizenship exam. And they connected with a long-established Huang family association in Chinatown, which was designed to help immigrants who share a last name (under the assumption that they’re somehow related). From this association, they bought a plot in a burial area pre-purchased for people named Huang at Hoy Sun Cemetery in Colma, about 10 miles south of the city.

It was managers at their Chinese senior apartment building who recommended Ashley & McMullen when my grandmother passed. (I learned later that Ashley & McMullen had taken over a Chinese funeral home called Wing Sun, as well as the Cathay Mortuary.) My Uncle Eddy and Aunt Alice took my grandfather there to plan the memorial service. He asked for a Buddhist ceremony that pulled out all the stops.

While some reviewers on Yelp have described Ashley & McMullen as overbearing in the way they dictate to families what should be done at funerals, Uncle Eddy told me he was actually glad they seemed to know all the rituals. I thought I was the only one who didn’t know what to do, so it surprised me to hear Uncle Eddy say he had never attended a Buddhist funeral.

My mom later told me that the ceremony my grandfather and I described to her involved Buddhist rituals more common to Southeast Asia than China. She clicked her tongue and complained that it would have been more proper to have monks chanting rather than nuns.

I wouldn’t know the difference. American Chinatowns tend to mash together ethnic Chinese traditions from different locations. I was just grateful to have something to do to express my respect for her. Funeral services, I guess, are more about comforting the living.

When we arrived at the cemetery in Colma, we did some more bowing with joss sticks. And then at the open gravesite, we each tossed in a black armband, a handful of dirt, and a red rose. When the casket was lowered, we ducked our heads because we weren’t supposed to watch.

And who led us through these actions at the cemetery? An African-American funeral director from Ashley & McMullen who came to show us, a bunch of apprehensive Chinese-Americans, what to do. As I walked over a lit newspaper bundle to symbolize the final crossing over, I thought about how my grandmother probably wouldn’t have expected her journey to end up here, like this, but she would’ve been happy to see we were in good hands.

is national & science editor of Zócalo Public Square.

Primary Editor: Andrés Martinez. Secondary Editor: Becca MacLaren.

Photos courtesy of Jia-Rui Cook.

Add a Comment