For as long as America has proclaimed itself a welcoming country of immigrants, policies have been in place to keep specific classes of people out. Naturalized citizenship was limited to “free white persons” until the 1860s, and Asians, for instance, weren’t allowed to be naturalized citizens until as late as the 1950s. From 1924 to 1965, immigration was controlled by ethnic quotas with per-country limits, which favored western Europe, and even certain countries in western Europe, and restricted almost everyone else.

The civil rights movement prompted a reassessment. In part to overcome the exclusion of southern and eastern Europeans, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, a bill that abolished the quota system and replaced it with a “preference system,” which took into consideration immigrants’ skills and family relationships with U.S. citizens or residents. The aim was to help reunite families, and to diversify the nation by making it easier for people outside of western Europe to come to America than ever before.

While the act was celebrated for decades, it’s clear now, 50 years later, that it also had unintended consequences. For example, by setting a cap on the number of immigrants from the Western Hemisphere that was actually significantly lower than the number of Mexicans who had been legally arriving in the U.S. at the time, it created a decades-long battle over illegal immigration across the U.S.-Mexico border.

So what is the 1965 Immigration Act’s true legacy? Has it shaped America for the better? In advance of the Smithsonian/Zócalo “What It Means to Be American” event, “How Did the 1965 Immigration Act Change America?,” we asked five immigration experts: Has the 1965 Immigration Act stood the test of time? What have been its weaknesses? What have been its strengths?

Primary Editor: Paul Bisceglio. Secondary Editor: Jia-Rui Cook.

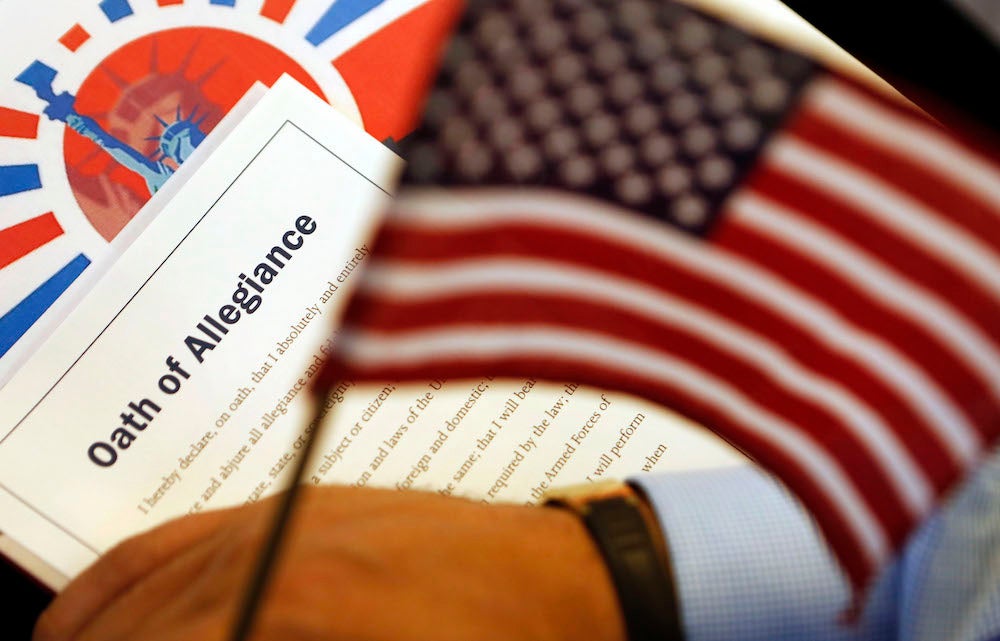

*Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Larry Downing.