The Cookbook That Declared America’s Culinary Independence

An 18th-Century Kitchen Guide Taught Americans How to Eat Simply but Sumptuously

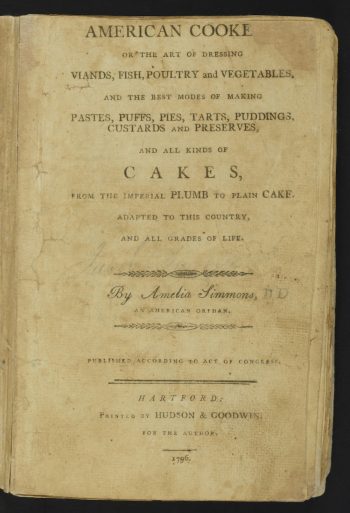

After the Revolution, Americans sought a national identity. American Cookery, the first cookbook written and published in the country, proposed one approach to American cuisine. Photo courtesy of Tomwsulcer/Wikimedia Commons.

American Cookery, published by the “orphan” Amelia Simmons in 1796, was the first cookbook by an American to be published in the United States. Its 47 pages (in the first edition) contained fine recipes for roasts—stuffed goose, stuffed leg of veal, roast lamb. There were stews, too, and all manner of pies. But the cakes expressed best what this first cookbook had to say about its country. It was a place that acknowledged its British heritage, to be sure—but was ultimately a new kind of place, with a new kind of cuisine, and a new kind of citizen cook.

The recipe for “Queen’s Cake” was pure social aspiration, in the British mode, with its butter whipped to a cream, pound of sugar, pound and a quarter of flour, 10 eggs, glass of wine, half-teacup of delicate-flavored rosewater, and spices. And “Plumb Cake” offered the striving housewife a huge 21-egg showstopper, full of expensive dried and candied fruit, nuts, spices, wine, and cream.

Then—mere pages away—sat johnnycake, federal pan cake, buckwheat cake, and Indian slapjack, made of familiar ingredients like cornmeal, flour, milk, water, and a bit of fat, and prepared “before the fire” or on a hot griddle. They symbolized the plain, but well-run and bountiful, American home. A dialogue on how to balance the sumptuous with the simple in American life had begun.

American Cookery sold well for more than 30 years, mainly in New England, New York, and the Midwest, before falling into oblivion. Since the 1950s it has attracted an enthusiastic audience, from historians to home cooks. The Library of Congress recently designated American Cookery one of the 88 “Books That Shaped America.”

The collection of recipes, which appeared in numerous legitimate and plagiarized editions, is as much a cultural phenomenon as a cooking book. In the early years of the Republic, Americans were engaged in a lively debate over their identity; with freedom from Britain and the establishment of a republican government came a need to assert a distinctly American way of life. In the words of 20th-century scholar Mary Tolford Wilson, this slight cookbook can be read as “another declaration of American independence.”

The book accomplished this feat in two particularly important ways. First, it was part of a broader initiative, led by social and political elites in Connecticut, that advanced a particular brand of Yankee culture and commerce as a model for American life and good taste. At the same time, its author spoke directly to ordinary American women coping with everyday challenges and frustrations.

The title page of American Cookery. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

American Cookery was a Connecticut project. There, a still mainly agricultural society of small independent farms was positioned to benefit from trading networks, near and far. But moving beyond mere subsistence farming required an openness to these new markets and to the world of commerce in general. Connecticut’s Federalist leaders were well-connected to influential newspapers, printers, and booksellers, and were able to promulgate a vision of an America where agriculture would flourish with the help of commerce—rather than in opposition to it.

Jeffersonians who disagreed with this outlook emphasized rural life as an end in itself. For them, the future of American society depended on the spread of the smallhold farmer, whose rustic simplicity would inoculate their fledgling country against the corrupting influence of the luxury to which Britain had succumbed.

The two camps took part in a public debate about luxuries—were they totems of prosperity or symbols of social decay? Some American thinkers, such as Joel Barlow, the author of the popular poem The Hasty Pudding, maintained that thoroughgoing simplicity should form the basis of American cooking and eating. But the Connecticut Federalists thought such asceticism left too little room for the aspirations of common people to improve their lot. These moderates preferred to encourage a kind of restrained gentility that would, in time, become the parlor rectitude of Victorian America. For those in the Federalist camp, encouraging education and the modest enjoyment of worldly goods would help build an enlightened society.

While their way of thinking was nothing if not temperate, the Connecticut Federalists promoted their views vigorously. They published Noah Webster’s popular Blue Back Speller (1783), the first American spelling book and primer, so called because of its cheap blue paper covers; Jedidiah Morse’s American Geography (1789), the first general compendium of political and geographic information about the new nation; as well as the writings of a literary circle known as the Connecticut Wits, whose poems allegorized the American Revolution and envisioned a glorious destiny for the new country. Many of these best-selling works were published by the firm of Hudson & Goodwin—which also published the first edition of American Cookery. Complementing this new American literary harvest were other ventures in locally-made goods. Imports were far from rare, but the message was clear: Everything—books, clothing, furniture, and even food—could be given an American slant.

With its new take on a practical topic, American Cookery caught the spirit of the times. It was the first cookbook to include foods like cranberry sauce, johnnycakes, Indian slapjacks, and custard-style pumpkin pie.

Moreover, Simmons had a keen understanding of the care that went into the construction of American household abundance. Behind every splendidly arrayed table lay the precise management of all the fruits and vegetables, meats and poultry, preserves and jellies, and cakes and pies that sustained the home and family—and American Cookery gave cooks and housewives tips for everyday cooking as well as occasions when the aim was to express greater gentility.

Simmons explained how to keep peas green until Christmas and how to dry peaches. She introduced culinary innovations like the use of the American chemical leavener pearlash, a precursor of baking soda. And she substituted American food terms for British ones—treacle became molasses, and cookies replaced small cakes or biscuits.

Above all, American Cookery proposed a cuisine combining British foods—long favored in the colonies and viewed as part of a refined style of life—with dishes made with local ingredients and associated with homegrown foodways. It asserted cultural independence from the mother country even as it offered a comfortable level of continuity with British cooking traditions.

American Cookery also carried emotional appeal, striking a chord with American women living in sometimes-trying circumstances. Outside of this one book, there is little evidence of Amelia Simmons’s existence. The title page simply refers to her as “An American Orphan.” Publishers Hudson & Goodwin may have sought her out, or vice versa: The cookbook’s first edition notes that it was published “For the Author,” which at the time usually meant that the writer funded the endeavor.

Whatever Simmons’s backstory might have been, American Cookery offers tantalizing hints of the struggles she faced. Although brief, the prefaces of the first two editions and an errata page are written in a distinctive (and often complaining) voice. In her first preface, Simmons recounts the trials of female orphans, “who by the loss of their parents, or other unfortunate circumstances, are reduced to the necessity of going into families in the line of domestics or taking refuge with their friends or relations.”

American Cookery asserted cultural independence from the mother country even as it offered a comfortable level of continuity with British cooking traditions.

She warns that any such young female orphan, “tho’ left to the care of virtuous guardians, will find it essentially necessary to have an opinion and determination of her own.” For a female in such circumstances, the only course is “an adherence to those rules and maxims which have stood the test of ages, and will forever establish the female character, a virtuous character.” Lest the point somehow be missed, Simmons again reminds readers that, unlike women who have “parents, or brothers, or riches, to defend their indiscretions,” a “poor solitary orphan” must rely “solely upon character.”

The book appears to have sold well, despite Simmons’s accusation on the errata page of “a design to impose on her, and injure the sale of the book.” She ascribes these nefarious doings to the person she “entrusted with the recipes” to prepare them for the press. In the second edition she thanks the fashionable ladies, or “respectable characters,” as she calls them, who have patronized her work, before returning to her main theme: the “egregious blunders” of the first edition, “which were occasioned either by the ignorance, or evil intention of the transcriber for the press.” Ultimately, all her problems stem from her unfortunate condition; she is without “an education sufficient to prepare the work for the press.” In an attempt to sidestep any criticism that the second edition might come in for, she writes: “remember, that it is the performance of, and effected under all those disadvantages, which usually attend, an Orphan.”

These parts of the book evoke sympathy. Women of her time seem to have found the combination of Simmons’ orphan status and her collection of recipes hard to resist, and perhaps part of the reason lies in her intimations of evil as much as her recipes. When the pennywise housewife cracked American Cookery open, she found a guide to a better life, which was the promise of her new country. But worry and danger lurked just below the surface of late 18th-century American life, especially for women on the social margins. In a nation still very much in the making, even a project as simple as the compilation of a cookbook could trigger complex emotions. American Cookery offered U.S. readers the best in matters of food and dining as well as a tale of the tribulations facing less fortunate Americans—including, it seems, the “American Orphan” Amelia Simmons herself.

Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald have written three books about New England food history. Their latest, United Tastes: The Making of the First American Cookbook, was published by the University of Massachusetts Press. Stavely and Fitzgerald are a married couple and live in Jamestown, Rhode Island.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Lisa Margonelli.

Add a Comment