The 19th Century Labor Movement That Brought Black and White Arkansans Together

In 1888, Small Farmers, Sharecroppers, and Industrial Workers Organized to Fight Inequality

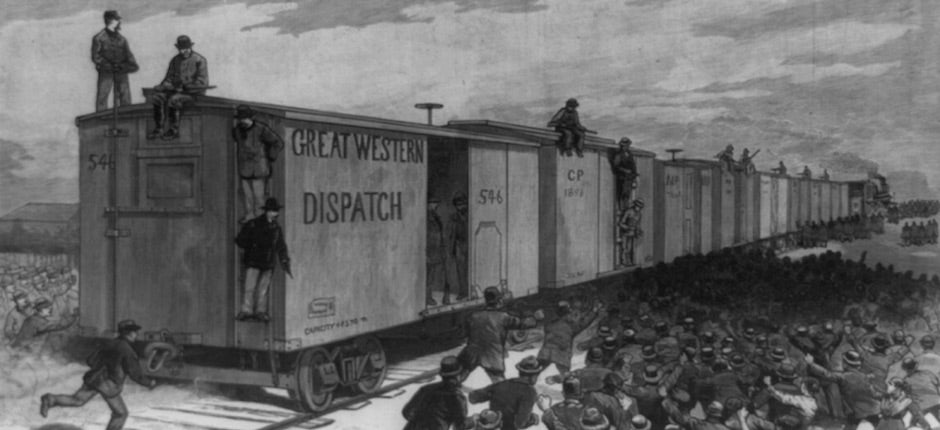

In 1886, Arkansas railroad workers joined the large regional strike targeting the Gilded Age financier and industrialist Jay Gould. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Today, when Americans think about the tradition of political protest to protect democracy, they often recall the mid-20th century, when millions of Americans participated in the civil rights movement and protests against the Vietnam War. But the roots of American grassroots political activism actually date back further to movements that contested the most basic democratic rights in the South during the late 19th century.

One place to see those roots is in the Gilded Age politics of Arkansas, then a hotbed of farmer, labor, and biracial political movements. The Arkansas story is about the awful means used by wealthier white people to consolidate the power of one party, the Democrats, which would prevail in the state until the 1960s.

One-party rule wasn’t new in Arkansas during the Gilded Age, which ran from the 1870s to about 1900. Arkansas was admitted into the Union in 1836. During the antebellum period, when one-quarter of the Arkansas population was enslaved, the Democratic Party dominated politics in the predominantly rural state.

But things changed in 1864 when Union forces established control of Arkansas, and a state constitutional convention appointed Unionist Isaac Murphy, a Republican, as provisional governor. A subsequent “rump election” supervised by Union troops, in which only 12,000 Arkansans voted, made Murphy a full-term, four-year governor. The GOP held the office for the next 10 years, throughout Reconstruction, during which time it made unprecedented efforts in behalf of public education for both races.

But the Republicans’ grip always seemed tenuous and fraught with danger. In 1868, when more than 20,000 black men in the state registered to vote, the Democratic-affiliated Ku Klux Klan went on a bloody rampage, killing more than 200 people. Most victims were African Americans, but Klansmen also killed white Republicans who had supported the Union during the war or had arrived recently as “carpetbaggers” from outside the South.

The one-party rule of the South was not as solid as it seemed. Instead, the Gilded Age saw the emergence of a third-party movement speaking for small farmers, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and industrial workers who felt squeezed by the “robber barons.”

About two weeks before national Election Day that year, Monroe County Democratic leader and Klansman George Clark shot two of the state’s leading white Republicans. Congressman James Hinds did not survive, but Joseph Brooks did. After losing a disputed gubernatorial election in 1872 to another Republican, Elisha Baxter, Brooks became a central figure in the Brooks-Baxter War, a small-scale intrastate civil war that itself resulted in more than 200 deaths. Political violence was becoming the norm in Arkansas.

The violence undermined the Republicans and the project of Reconstruction. The Democratic Party regained the governor’s office in 1874 and faced little serious competition for the next dozen years, with the moribund Republican Party failing to nominate a candidate in 1878 or 1880. Thus began the “Solid South,” marked by Democratic dominance for about a century. But the one-party rule of the South was not as solid as it seemed.

Instead, the Gilded Age saw the emergence of a third-party movement speaking for small farmers, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and industrial workers who felt squeezed by the “robber barons” who were gobbling up bigger shares of the wealth. These farmers and workers began organizing to improve their lot.

Labor strife became common throughout the nation during the Gilded Age, and Arkansas was no exception. In 1886, Arkansas railroad workers affiliated with the national Knights of Labor union participated in the “Great Southwestern Strike,” a large regional effort that targeted the financier and industrialist Jay Gould. In 1888, coal miners in the western part of the state walked off the job too. Some 1,400 Arkansas coal miners took part in the national miners’ strike of 1894. Black farmhands, meanwhile, went on strike at a plantation just south of Little Rock in 1886.

The movements also inspired new third parties in Arkansas. The first such party, the Greenback-Labor Party, sought to address a tightening currency supply and monopolistic business practices. It made unsuccessful, often downright feeble, challenges in state and congressional elections from 1878 to 1882 before disintegrating.

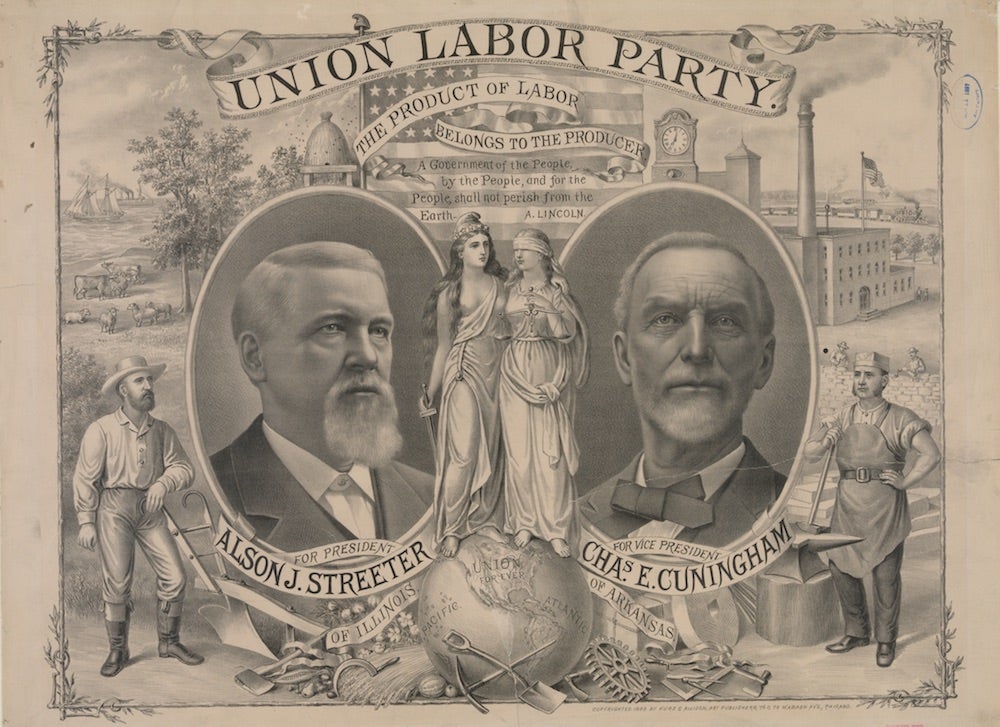

Two farmers’ groups, the Brothers of Freedom and the Agricultural Wheel, emerged in its wake—and, with the Knights of Labor, soon became involved in Arkansas politics. These groups were first formed on a nonpartisan basis, but, in 1888, they became supporters of the Union Labor Party, an ostensibly national third party that focused on addressing the currency and credit crunch that vexed many farmers and workers, regulating the railroad and telegraph industries, and, in southern states like Arkansas, abolishing the convict lease system whereby states supplied corporations with dirt-cheap convict labor. White men occupied the top positions of leadership in the Union Labor Party, but black men participated in party conventions and ran for offices under its banner.

So, with the elections of 1888, Arkansas Democrats faced their first serious challenge since the end of Reconstruction, from a biracial coalition that would speak for the working classes. The Democrats responded with violence and chicanery that made a mockery of democracy and the Constitution. In the state’s first and second congressional districts, Union Labor candidate L.P. Featherston and the Agricultural Wheel-supported Republican candidate John M. Clayton were both, in the parlance of the day, “counted out” of victories by Democrats, who either stuffed ballot boxes or stole them. Both men contested the results before the U.S. House of Representatives, which ruled against the Democrats in each case. Only Featherston took his seat in Congress, however; Clayton died while gathering evidence in Conway County, the victim of an apparent assassination arranged by Democrats.

A Union Labor Party campaign poster shows Arkansas’s Charles E. Cunningham (right), the party nominee for vice president in 1888. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In the governor’s race, Democrat James P. Eagle defeated the Republican-backed Union Labor candidate Charles M. Norwood by a margin of about 8 percent. Union Labor leaders protested the outcome—to no avail—providing evidence that Democrats had intimidated voters (especially black men) and engaged in ballot box thefts in Union Labor strongholds. In 1890, with the continued cooperation and support of Republicans, the Union Labor Party again challenged the Democrats, adding a demand for a “free ballot and fair count” to its platform of anti-monopolistic reforms. Yet again it met with defeat, as Democrats waged another campaign of intimidation, violence, and stolen or stuffed ballot boxes. This time, defeated Union Labor congressional candidates did not look to the U.S. House of Representatives for help, since Democrats had taken control of that body in the elections and were unlikely to unseat fellow party members.

The abuses continued. In 1891, the Democratic-controlled Arkansas state legislature passed an “election reform” law that virtually disenfranchised those who could not read, which according to the 1890 census included 13 percent of white men and 56 percent of black men aged 20 or over. That same year, black labor activism also suffered when a strike by cotton pickers over low wages at a Lee County plantation became violent, resulting in the deaths of at least 14 black men and one white man.

Not surprisingly, voter turnout in Arkansas dropped by nearly 20 percent in 1892. By then, the Union Labor Party had given way to the national (but primarily western and southern) Populist Party. Republicans also started fielding their own tickets again, but the party remained weak and Democratic candidates won easy victories in Arkansas state and congressional elections. Still, the violence persisted: Election officials in Calhoun County participated in a riot in 1892 that left at least four black men dead.

The state legislature also continued its assault on voting rights by passing a poll tax law, which the diminished electorate ratified that year. The Populist Party participated in state elections until 1906, but it never posed a serious threat to the Democratic Party. Some ex-Populists drifted into the Socialist Party, which held its first state convention at Little Rock in 1903. The Socialists fared even worse at the ballot box than the Populists had; their most notable success was the 1912 election of Pete Stewart, a United Mine Workers of America leader, as mayor of Hartford, a coal mining town in Sebastian County. In spite of—or perhaps in response to—such efforts, the violent suppression of the working classes continued in Arkansas. As late as the mid-1930s, black and white sharecroppers who joined the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, organized in Poinsett County, frequently faced violent attacks, and in some instances were murdered.

Gilded Age Democrats, willing and able to do anything they deemed necessary to maintain power, had started a wave of violence, election theft, and disenfranchisement that would last a century. Such tactics allowed the Democratic Party to cement its dominance of Arkansas politics and assured that healthy democracy could not flourish. Not until 1966, when Republican Winthrop Rockefeller defeated Democrat James D. Johnson, would the Democrats’ 92-year stranglehold on the state’s governorship finally end.

Matthew Hild is a lecturer of history at Georgia Tech. He is the author of Arkansas’s Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest.

Buy the Book

Skylight Books | Powell's Books | Amazon

PRIMARY EDITOR: Eryn Brown | SECONDARY EDITOR: Joe Mathews

Add a Comment