In 1634, 27 years after English colonists landed at Jamestown, a group of entrepreneurs and adventurers led by Leonard Calvert, son of the 1st Lord Baltimore, sailed forth on the ships Ark and Dove to establish the Maryland colony.

They named their new capital St. Mary’s City to honor the Virgin Mary. Catholics like the Calverts had experienced religious persecution in England, and soon they issued a proclamation extending freedom of worship to all (Trinitarian) Christians. This then-radical announcement established the Maryland colony’s reputation as the birthplace of the American values of religious tolerance and separation of church and state. Today, Historic St. Mary’s City, recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1969, is a living history museum and sits alongside St. Mary’s College of Maryland on a peninsula bordered by the Potomac and Patuxent rivers and the Chesapeake Bay at the southernmost tip of the state.

The early colonists were welcomed by indigenous peoples who had inhabited the Chesapeake, one of the richest ecosystems in the world, for thousands of years. Unlike the Powhatan in the Virginia colonies, the Yaocomico and Piscataway offered the new arrivals shelter and sought a relationship of mutual benefit. The ensuing shift from virgin woodland to tobacco plantations was swift and seismic in its impact on the peoples and land.

But once colonial culture became dominant and the transition to tobacco agriculture, fishing, crabbing, and oystering was complete, the pace of life in St. Mary’s slowed. Political upheaval in 1694 resulted in removal of the Maryland capital from St. Mary’s City to Annapolis, and the area began to earn its reputation as a rural “backwater.”

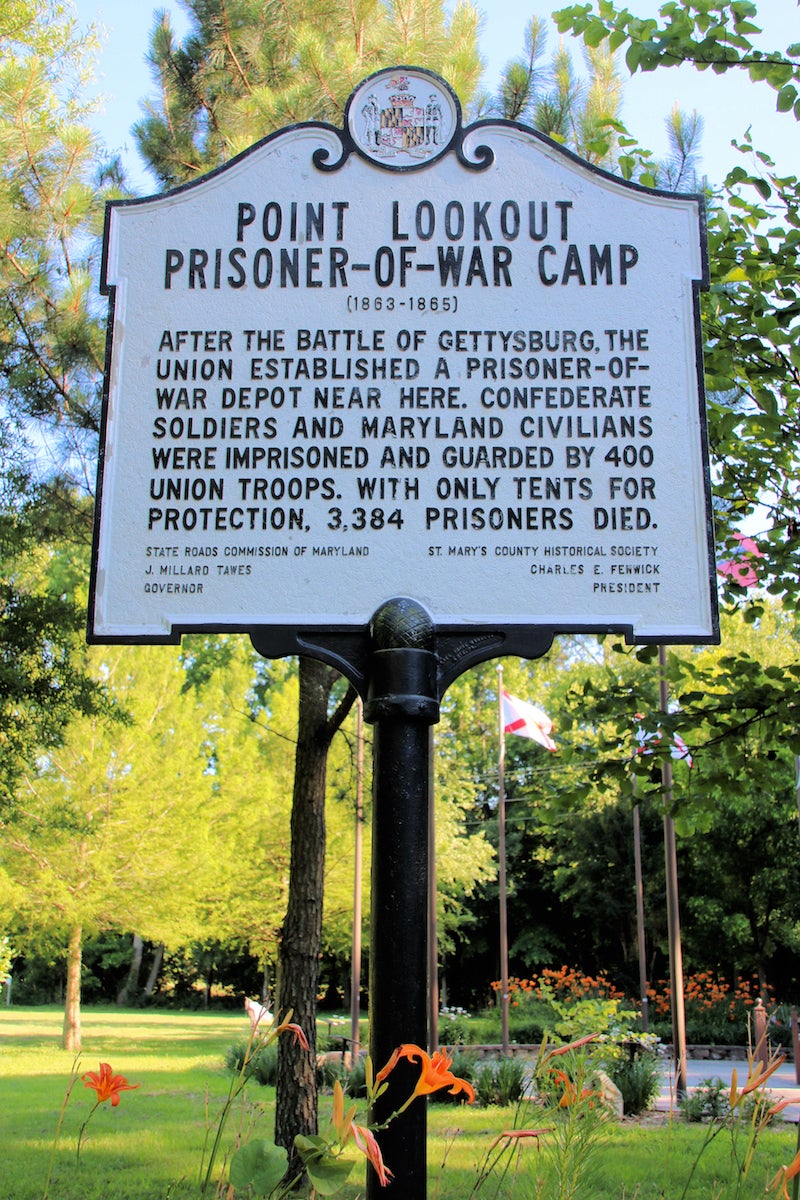

For over 300 years, St. Mary’s County was a place marked by tradition and continuity. Yes, the place experienced fluctuating tobacco prices, wartime attacks by the British in 1776 and 1814, the Civil War and emancipation of Maryland’s enslaved persons, and almost a century of “oyster wars” between Maryland and Virginia watermen. But St. Mary’s remained isolated and parochial.

That changed with the arrival of World War II and the establishment of the Patuxent River Naval Air Station. As job opportunities increased, the population grew in number and diversity. The economic shift generated by the Navy’s arrival continues to fuel and shape development in the country today.

What was once an isolated, rural community of farmers, watermen, and small business owners, deeply rooted and slow to change, is now a fast-growing “high-tech corridor.” Naval aerospace and defense contracting dominate the county economy. The area is rapidly transitioning from rural to suburban and has all the environmental challenges, problems, and cultural shifts one would expect in a burgeoning population. As with any great economic shift, as ways of life change, people do not benefit equally from the changes. Hidden inequities and deep social and political divides remain here.

Traveling St. Mary’s roads and waterways today, it’s possible to glimpse vestiges of the past scattered between the new housing developments springing up in former tobacco fields. You can see weathered tobacco barns, former oyster shucking houses, and tumbling-down farmhouses, many in the process of being reclaimed by vegetation. Memorials, monuments, and plantation structures marking the scars of slavery and a war between neighbors reveal a contested history.

Thriving farms still exist here and there. And the rivers and Bay remain, still worked by watermen, though their catch is estimated at one percent of historic levels. The families in St. Mary’s County include those whose ancestors came over on the Ark and the Dove, along with descendants of indigenous peoples, enslaved persons, and slave owners, as well as recent arrivals who have come to join the workforce at the Pax River Naval Air Station. For the former, the historic landscape is full of memories; for the latter, that landscape is full of opportunity for discovery.

Merideth M. Taylor is professor emerita of Theater, Film and Media Studies at St. Mary’s College and author of Listening In: Echoes and Artifacts from Maryland’s Mother County, in which some of these images appear.

BUY THE BOOK

Skylight Books | Powell’s Books | Amazon

Primary Editor: Joe Mathews | Secondary Editor: Lisa Margonelli

Add a Comment