The setting is the piney woods of Civil War Jones County, Mississippi. The white farmer Newt Knight leads a band of deserters against Confederate forces. An enslaved woman, Rachel, lends invaluable aid to this Knight Band. After gaining her freedom, she spends the rest of her life as Newt’s partner.

These events are a great story—and even better history. This summer, Free State of Jones will bring to movie theaters across the country a thrilling and relatively unknown tale of Civil War insurrection, romance, and interracial collaboration. The film, inspired by several historical books about these events including my own, shows how far scholarly research—and popular entertainment—about the Civil War has come.

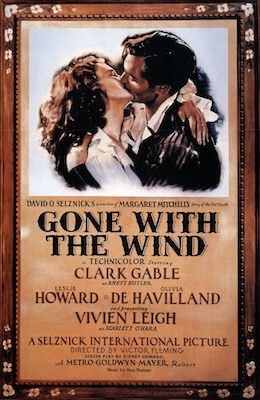

Free State of Jones is a Civil War movie that privileges neither Gods and Generals nor genteel plantations à la Gone with the Wind. White yeoman farmers represented a class disproportionately devastated by battlefield deaths and Confederate seizures of home front produce and property. As they increasingly desert the Confederate army, an inner civil war erupts in Jones County between the Knight Company and Confederate troops. Soon, fathers, mothers, wives, and children join forces to defend and hide deserters from authorities. Meanwhile, social disorder empowers slaves and runaways, offering the promise of true and lasting freedom.

In the movie, class and race converge when the deserter Newt is run down and mauled by the Confederacy’s “nigger hounds.” Taken to the swamps by Rachel, he encounters Maroons, escaped slaves who formed clandestine communities, for the first time. “Are they runaways?” Newt asks Rachel with hesitation. “Ain’t you runnin’?” she responds. The interracial alliance is born.

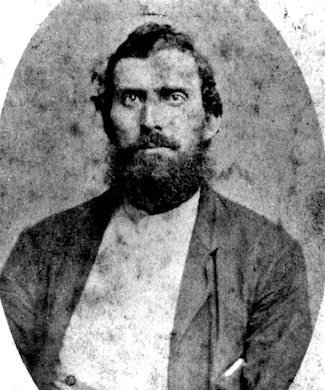

Newton Knight, 1837–1922.

The events in Jones County demonstrate a larger truth of dissent and violence that erupted throughout the South during the Civil War. This research presents a crucial corrective to the Lost Cause version of history that afflicts us still—not simply in movies and novels, but also in the classroom, where even my college students have frequently assured me that “Granny said our slaves were treated just like family in the old days,” or on internet message boards and chat rooms, where self-proclaimed authorities insist the Civil War was never really about slavery.

Scholars like myself have long struggled against this version of Civil War history. It was created only around the turn of the 20th century, when a few influential Northern and Southern historians strove to heal the war-damaged United States by creating a more conciliatory vision of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Denouncing the war as a needless slaughter brought on by politicians, historians such as William Archibald Dunning and his followers portrayed the Reconstruction that followed as a tragic era of “Negro rule,” carpetbagger corruption, and scalawag treason. The Dunning School soft-peddled slavery’s role as the major cause of war. The myth of a Civil War fought over “states’ rights” hardened into orthodoxy, providing a “noble cause” for white Southerners seeking to sanctify the sacrifices and deaths of their ancestors.

Hollywood soon celebrated the Lost Cause version of the war in its 1915 production of Birth of a Nation. Directed by D. W. Griffith, and the most technologically-advanced movie of its time, this film glorified Ku Klux Klansmen as rescuers of virginal white womanhood from black male rapists portrayed as little better than beasts. In the process, the movie legitimized segregation and lynching as tools of racial control.

Some scholars fought back against the flawed history of the early 20th century. In 1935, W.E.B. Du Bois eviscerated Lost Cause orthodoxy with his masterful, now classic book, Black Reconstruction in America. Du Bois pulled no punches in describing the political corruption and white terror that dominated Reconstruction. Few people, however, read Black Reconstruction before the 1960s. Du Bois held a Ph.D. from Harvard, but he was a man of color. In 1930s America, where racial segregation relegated people of color to second-class citizenship and black men were lynched with impunity, a historian of African-American ancestry—especially a politically far-left one—had little credibility, even among educated whites. With notable exceptions, white academics dismissed Du Bois’s challenge to prevailing historiography with faint praise and sometimes outright contempt.

Historian C. Vann Woodward, one of those few who praised Du Bois’s work, refuted Lost Cause history again in his own 1951 book, Origins of the New South. Yes, Woodward asserted, slavery had caused the Civil War; yes, Reconstruction was a tragic era—not because of “Negro rule,” but rather because a resurgent, corrupt, and violent Democratic Party thwarted the promise of racial equality through violent campaigns to restore white supremacy.

Other historians soon followed Woodward’s lead. By the 1960s, the Lost Cause was on its way to the ash heap of history.

But academic historians could not expunge its appeal in popular culture. MGM’s blockbuster production Gone with the Wind hit the theaters in 1939, four years after Du Bois’s work. The movie continued to enjoy enormous popularity for decades after. In 1960, at age 13, I saw it for the first time at one of its many special theatrical showings. Immediately afterward, I bought the novel by Margaret Mitchell that inspired it.

Gone with the Wind won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1940.

As a teenager attracted to fantasies of a mythical past, I learned from Gone With the Wind almost all that I knew about the Civil War. The romantic haze of gracious plantations, men of honor, Southern belles, and happy, loyal slaves softly shrouded the movie’s images of degraded poor whites, uncivilized and “uppity” freedpeople, and a benevolent Ku Klux Klan.

Other Hollywood productions kept up the image. In 1948, Universal Pictures dared to produce Tap Roots, a movie based on James Street’s novel of the same name and inspired, Street claimed, by the Free State of Jones. Whereas Street’s topic was Southern Unionism, however, the film served little more than a warmed-over Gone With the Wind. It highlighted—you guessed it—men of honor, Southern belles, and happy, loyal slaves.

The ultimate distortion of Jones County’s insurrection came in a 1951 book by Ethel Knight, The Echo of the Black Horn. A descendant of the pro-Confederacy side of the Knight family, Ethel anchored the story of Newt and Rachel firmly in Lost Cause principles and the segregationist code of the 1950s South. She rendered Newt an outlaw, a murderer, and a sinner who practiced racial amalgamation. Rachel, she told readers, was sexually promiscuous and practiced witchcraft. She had charmed Newt across the color line.

Such was the story that came before my eyes in 1992 when I read Knight’s book for the first time. Fascinated, I discovered that no fully researched history of Newt, Rachel, and the Jones County insurrection had ever been published.

I began to research, propelled by key questions. I wondered what drove the Jones County insurrectionists to support the Union. Were they opposed to slavery, at least some of them? What roles did class, religion, kinship, and local events play in fomenting conflict? I expected to find women, children, and enslaved people involved in this home front war, as I had in my earlier work on the Civil War in North Carolina, and I did.

By the time I embarked on this work, Civil War historians had built on the legacy of Du Bois and Woodward to examine the myriad ways in which conflicts over slavery led directly to the Civil War. The white South, they concluded, was anything but “solid.” Dissent and outright opposition to the Confederacy erupted time and again in regions with large non-slaveholding populations.

In recent years, too, Hollywood’s treatment of the Civil War has advanced well beyond Gone with the Wind with movies like Glory, Cold Mountain, and Lincoln. Yet, popular culture has shown us little about the Southern families that rejected secession from the Union and made war on the Confederacy.

Gary Ross, director of Free State of Jones, and Victoria Bynum on the set for her cameo role in the film.

Free State of Jones adds to our knowledge of Southern dissent within evolving depictions of our nation’s bloodiest conflict. Gary Ross, the movie’s screenwriter and director, read widely and deeply about the history of the Civil War and Reconstruction. This movie counters Lost Cause romanticism at every turn. It replaces the “honor” of benevolent slaveholders with the righteous anger of yeoman farmers, the rustle of crinoline slips with the click of rifles cocked by farm girls, and the contented faces of loyal slaves with the wary countenances of Maroons living in swamps. All rise to claim their rights in this tale of a rich man’s war and poor man’s fight. The movie reminds us that for a majority of Southerners, the Civil War was ultimately about class survival and racial liberation.

is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History at Texas State University, San Marcos and the author of The Free State of Jones (2001, 2016), and The Long Shadow of the Civil War (2010), both published by the University of North Carolina Press. Her blog, Renegade South, serves as a repository for new information about Southern Unionism and Southern mixed-race communities.

Buy the Book: Skylight Books, Powell's Books, Amazon.

Primary Editor: Siobhan Phillips. Secondary Editor: Callie Enlow.

*Lead photo courtesy of STX Entertainment. First interior photo courtesy of Mississippi History Now/Wikimedia Commons. Second interior image courtesy of Crisco 1492//Wikimedia Commons. Third interior photo courtesy of Victoria Bynum.

Add a Comment