Over the last few years, the idea of “the one percent” has become a popular way to discuss the gap between the fantastically wealthy—the one percent of Americans who control more than 20 percent of the country’s wealth—and the rest of us. But the one percent is not a new phenomenon. Back in 1900, they were known as the Robber Barons—people like Andrew Carnegie and Philip Armour, who were riding new industries and monopolies to ever greater fortunes. At the top of them all sat John D. Rockefeller, founder of Standard Oil, who virtually invented the model of a vertically integrated, globe-spanning corporation.

But the Robber Barons had a corrective: Ida Minerva Tarbell countered them by inventing the calling and the career that has become known as investigative journalism. Her dogged research helped provide a foundation for anti-trust law, triggering the breakup of Standard Oil and sullying Rockefeller’s reputation forever. Just as the rich are still with us, so are the investigative reporters.

I have been an investigative reporter for 45 years. When I became executive director of the group Investigative Reporters and Editors in 1983, I realized I had to be a spokesperson for several thousand of us and I needed to learn more about the early 20th-century journalists known as the Muckrakers—people like Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, David Graham Phillips, and Paul Y. Anderson, who laid the groundwork for our field. Among them, there was one woman: Tarbell.

On the surface, Tarbell seemed an unlikely figure to rock the world of the Robber Barons. She was not born to an influential family; she was an independent woman at a time when women had few options beyond wife, mother, or schoolteacher; and she was a late bloomer—age 37 before she found her footing as an editor and reporter. She was a thoroughly modern woman, though she had died four years before I was born. I was fascinated because the quality of her journalism was astounding by any standard—and especially during an era of no open records laws, no photocopy machines, almost no telephone service, no air travel and few roadways or automobiles, and widespread resistance to women doing journalism.

I started by visiting the nearby University of Missouri library. There, a dusty copy of Tarbell’s innocuously titled expose, The History of the Standard Oil Company, awaited me. The book had not circulated for three decades; it contained the serialized investigation of Rockefeller and Standard Oil that appeared month after month in McClure’s magazine from 1902 to 1904, all combined into an expanded book version of 815 pages. Although published in 1904, the book read as if written the previous week, given its richly documented narrative about how a brilliant entrepreneur created a behemoth from scratch, then allowed his pride and greed to push him into moral and legal ambiguity. Tarbell’s commitment to transparency and public knowledge inspired me. After years of research, she spent two hours anonymously watching Rockefeller in church to complete a character study of him. “A man who possesses this kind of influence cannot be allowed to live in the dark. The public not only has the right to know what sort of man he really is; it is the duty of the public to know.”

Tarbell was born in Hatch Hollow, Pennsylvania, in 1857. Two years later, the first oil well in the U.S. began spewing “black gold” within a few miles of her home. Tarbell’s parents started manufacturing oil barrels from wood. After all, the oil had to be captured and shipped. But neither shipping containers nor pipelines nor barges nor railroad cars to hold the messy liquid existed yet.

The sticky goo and stench and noise related to digging, extracting, and transporting oil from wells defined Tarbell’s childhood. She and her siblings often came home from play covered in oil after a neighborhood driller hit a gusher. Tarbell’s parents opened the family home to people, often strangers, badly burned or otherwise injured because of their carelessness around a substance that ignited easily. Funerals in the aftermath of oil well explosions and fires occurred often around Hatch Hollow and the nearby city of Titusville. Every day the local gossip was about one get-rich-quick hustler or another. One standout—not a huckster, but a young man with a business plan—was John D. Rockefeller, 18 years older than Ida Tarbell, with a base in relatively nearby Cleveland.

Ready to escape oil, at least temporarily, Tarbell was the only woman (along with 31 men) to enter Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania. Tarbell excelled as a student. Because of her good looks combined with her good nature around “the boys,” she mostly escaped being treated as a “mere” woman, a risk she had worried about, given her pioneering status. Upon graduation, she vowed to make the world a fairer place than the society she had entered at birth. She wanted to transcend the “normal” options for women of her station during her era—marriage with motherhood, or elementary school teaching. The question was how to achieve her big ambitions.

For the next 20 years, Tarbell held a variety of poorly paid, dead-end teaching jobs with stretches of unemployment. She finally decided her best bet was to leave the country. In 1891, when she was 34, Tarbell reluctantly left her family in Pennsylvania and sailed to Paris, France, to be a graduate student and freelance writer. In one published article, she compared what she deemed the scourge of alcoholism across the United States with responsible consumption of alcohol in France.

Samuel Sidney McClure took notice of her work. McClure, a brash, idealistic Irish immigrant who founded an eponymous monthly magazine based in New York City, decided to lure Tarbell back to the United States and give her a job as a staff writer undertaking serious topics.

At the time, Americans were worrying about the economic dominance of gigantic monopolistic corporations legally known as “trusts.” Rockefeller’s Standard Oil trust controlled almost the entire oil extraction, refining, and gasoline industry, while other trusts dominated the steel, beef, and sugar industries. There was a general feeling that while the trusts might be making money legally, their monopolistic practices might be unfair, and might be stifling competition. When McClure’s decided to investigate the alarming reach of trusts, Standard Oil became the logical focal point.

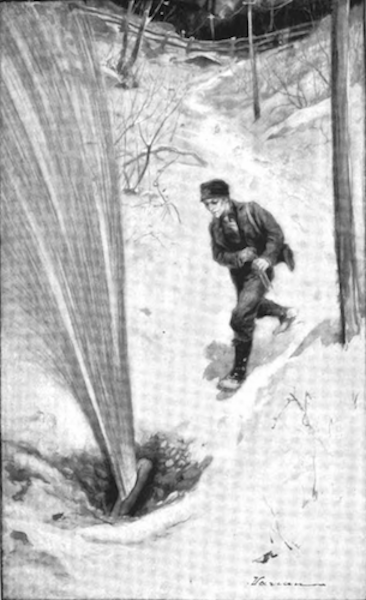

Illustration of a pipeline break from Ida Tarbell’s influential 1904 book, The History of the Standard Oil Company.

Because of her background in northwest Pennsylvania, combined with her research skills and her fearlessness, Tarbell seemed to McClure like the obvious choice. Tarbell’s father worried that she or the magazine would get hurt, somehow, by Rockefeller, but Tarbell scoffed at mentions of danger. She mapped out a plan to gather information, starting with congressional and state legislative testimony, then working backwards to find more published facts plus former employees who could speak about their knowledge without fear of losing their jobs. She traveled alone, seeking interviews with industry executives and government officials, as well as requesting obscure documents from dusty archives. She pretty much invented the relentless gathering of sensitive written information and sources that investigative reporters now call “paper trails” and “people trails.”

Month after month, readers of McClure’s watched the evidence accumulate, discussing the articles at the dinner table and club meetings. Tarbell untangled how Rockefeller led Standard Oil to dominance, explaining that he parlayed the trust’s control of oil resources to pressure railroads to ship products at low rates unavailable to his competitors. Tarbell’s painstakingly documented proof that Rockefeller had created an unfair playing field favoring Standard Oil and punishing competition seemed shocking at the time. Because railroads served much of the nation then as the primary means of passenger and commodities transportation, Americans tended to think of those railroads as public utilities. That Rockefeller had established unfair advantage inside the railroad realm came across as a betrayal.

Congress quickly approved new oversight of trusts. President Theodore Roosevelt pushed for increased anti-trust powers; he encouraged his attorney general and locally based federal prosecutors to rein in Standard Oil. During 1911, the United States Supreme Court’s justices, clearly aware of Tarbell’s expose, forced a splintering of the Standard Oil trust into many different companies, among them Exxon and Mobil, which continued to compete against each other until recently.

In the years after her Standard Oil exposé, Tarbell expanded her expertise to publish about workplace safety and women’s rights and corporate reform, due to her intense curiosity and her strong belief in fair treatment for wage laborers. The U.S. has always celebrated its millionaire and billionaire entrepreneurs; but what makes America special is that we also celebrate the public’s right to know how that money is made.

is author of eight books, including Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller. He is currently writing a biography of Garry Trudeau.

Primary editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary editor: Jia-Rui Cook.

*Lead photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. Interior photo courtesy of Ida Tarbell, The History of the Standard Oil Company (1904).

Add a Comment