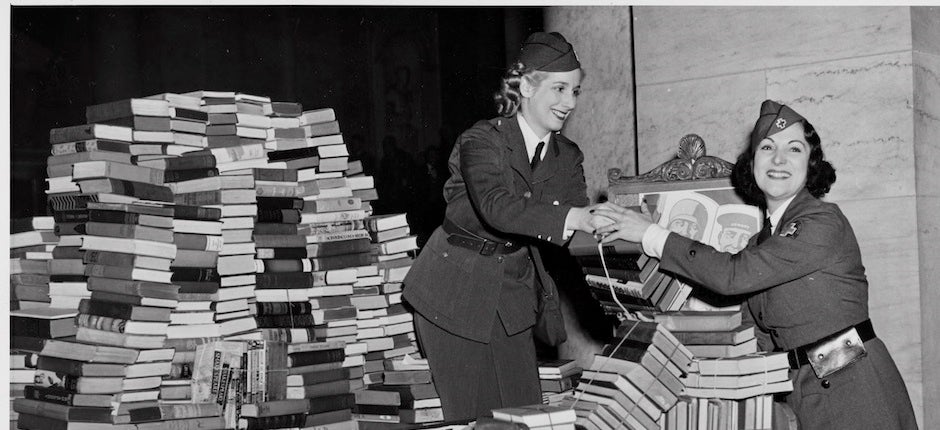

In January 1942, thousands of New Yorkers gathered on the steps of the legendary New York Public Library, at 5th Avenue and 42nd Street, wearing their Sunday best and warmest coats. When standing room became scarce, crowds formed across the street. Nearly everyone had at least one book in hand. These were not overdue, nor did they need to be returned to the library; instead they were “Victory Books,” bound for soldiers overseas.

It may be difficult to appreciate the significance of a book drive held nearly 75 years ago. But this was no ordinary campaign. At the time, books—vehicles for new ideas—were being banned and burned in Europe by the German Army. As the Nazis swept through Europe—occupying Poland, France, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Denmark—restrictions were placed on the authors and titles that could be read in these conquered territories; books by American, British, and Jewish authors were outlawed. The most severe penalty for being caught with such contraband was death. This threatened punishment produced Germany’s desired effect: Strict compliance with the book bans was the norm.

With this threat across the Atlantic, Americans felt an urgent need to preserve books and all they symbolized. To spread this message, Hollywood celebrities, popular musicians, politicians, and military officials visited the New York Public Library in January 1942 to give speeches and performances that were broadcast nationwide over the radio. Katharine Hepburn, Chico Marx, Benny Goodman, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, Wendell Willkie, and Danny Kaye were among the famous who visited the library. They stressed that the best defense against Germany’s war on books was to do the opposite: read and spread information. And so books became a sort of weapon in the war—fighting ignorance, censorship, and boredom.

In 1942, the New York Public Library stressed that the best defense against Germany’s war on books was to do the opposite: read and spread information.

The Victory Book Campaigns of 1942 and 1943 enlisted ordinary Americans and their favorite books. Librarians across the United States scattered giant bins in stores, movie theaters, train stations, schools, and other public spaces to collect “Victory Books” for those serving in the Army and Navy. In 1942, 10 million books were collected by the Victory Book Campaign, making it the largest book drive in the world. Another 8 million books were collected the following year.

Most of the donations were hardcover books, a reflection of the American book industry at the time. The majority of American publishers refused to enter the paperback trade, fearful that 25-cent softcovers would ruin the handsome profit margins they earned from hardcover sales. The donated hardcovers were fine for stationary Army camps in the United States and aboard Naval ships, where soldiers did not need to carry all of their belongings on long marches or into battle. When Americans shipped out to North Africa in 1942, they brought Victory Books to pass the long weeks spent sailing to their destination. Lacking any other entertainment, most tucked books into their packs and carried them into the invasion and beyond. But, long marches with aching backs and blistered feet caused many to whittle down the possessions they carried; heavy hardcovers were reluctantly tossed.

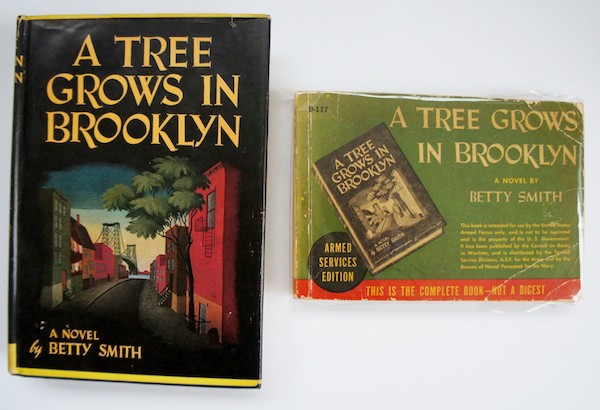

American publishers heard of the insatiable demand for books overseas and the plight of the ill-suited hardcovers. They banded together to create books specially designed for American sailors and troops. Scrapping the hardcover, using lightweight paper akin to newsprint, reducing page margins, eliminating blank pages, and shrinking the size of books to as small as 3.5 by 5.5 inches, publishers created volumes sized to fit the pockets of uniforms. These miniature paperbacks were called “Armed Services Editions,” and were sold to the military at cost; they were distributed, free of charge, to Americans serving overseas. Westerns, sports stories, histories, bestsellers, fiction, nonfiction, short stories, books of humor, and poetry—the range of subjects ran the gamut. Soldiers devoured them. Creased covers, loose pages, taped bindings, and dog-eared pages were evidence of their popularity. No matter how worn, the books were passed from one GI to the next. According to one soldier, “To heave one in the garbage is tantamount to striking your grandmother.”

Homesick and lonesome soldiers found solace in books. Surprisingly, Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was the most popular of them all, despite being a coming-of-age tale from the perspective of Francie Nolan, a young girl. Troops related to Francie’s difficult upbringing, her discovery of comfort and escape in books, and her resolve to beat the odds and achieve her dream of going to college. Smith received over 10,000 letters of gratitude from Americans in uniform. In one letter, a marine described watching his friend’s final moments of life and said a part of him died with his friend. However, two years later, Smith’s book transformed him and his heart “turned over and became alive again.” Another man wrote Smith that her book inspired him during difficult battles, and that he and his wife vowed to name their first-born daughter “Betty Smith,” to honor the author who helped him survive war.

Surprisingly, Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was the most popular novel among American soldiers.

Other books were appreciated for their ability to amuse. Leo Rosten, author of The Education of Hyman Kaplan, received a letter of praise from a unit stationed in the Persian Gulf, whose only other entertainment was “a ping-pong set—with one paddle only.” Rosten’s humorous tales became the hottest commodity on the post; the men assembled each night by campfire and “roared” with laughter as they read one Kaplan story per day—it was their “ration on pleasure.”

Publishers received letters suggesting future titles to be printed. One man explained that the books that were in the highest demand had “at least an essence of—to put it bluntly—sex and a lot of it.” He asked for Forever Amber, Strange Fruit, and Tiffany Thayer’s The Three Musketeers, as they were all endowed with that quality. One man wrote: “For days, I’ve been hunting through our service club, bothering the Red Cross, scanning our library shelves and hunting unrelentlessly through the barracks—for what????” He desperately wanted a copy of H. Allen Smith’s Low Man on a Totem Pole, a popular book of humor. Another soldier summed up the success of the publishers’ Armed Services Editions: “You have no idea how many hours of pleasure your books give to us.”

The German Army, by V-E Day, had burned an estimated 100 million books and destroyed hundreds of libraries, institutes, and rare book collections across Europe. By contrast, American librarians and publishers distributed over 140 million Victory Books and Armed Services Editions to those serving in the U.S. Army and Navy. These books made a lasting impact on the Americans who read them. Thanks to the Armed Services Editions, 12 million veterans returned home with an insatiable appetite for paperbacks. Demand was so high that publishers could not ignore this new market. A scant 200,000 paperbacks were printed in the United States in 1939; a staggering 95 million paperbacks were printed in 1947. Publishers realized they could earn a profit off paperbacks after all. In doing so, they printed books that attracted a larger audience of book readers than expensive hardcovers could.

A soldier enjoys a paperback in a flooded camp.

Besides revolutionizing the book industry, the provision of books to those in the armed forces also changed attitudes towards higher education. Before the war, most Americans did not dream of going to college; expensive tuition made it a financial impossibility. However, the passage of the GI Bill, which promised a free education on the government’s dime, coupled with a newfound interest in books and learning led many veterans to consider returning to school. After all, they had proven to themselves that they enjoyed the scholarly activity of reading even under the stresses of war. Over 2 million Americans pursued an education under the GI Bill.

The next time you see a tattered paperback, think of the millions of Americans in uniform who cherished them while at war. These Americans not only fought and won a military victory against the Axis powers; the reading habit they gained led to the democratization of higher education and access to books at home.

is author of The New York Times best-seller When Books Went to War: The Stories that Helped Us Win World War II. With a master’s degree in American History from the University at Albany and a law degree from the Cardozo School of Law, she is currently a staff attorney at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary Editor: Jia-Rui Cook.

*Lead photo courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Photo of soldier courtesy of Australian War Memorial.

Add a Comment