Published in 1946, John Hersey’s Hiroshima, which described the impact of the atomic bomb on residents of the city, is an extraordinary book. It not only described the bomb’s effects, it enabled Americans to see the Japanese people as fully human, even in the immediate wake of a war in which the Japanese had been demonized as a race.

Hersey’s perspective had roots in his childhood in China, where his parents were American missionaries. His capacity for empathic identification with even an enemy people was widely shared by a generation of missionaries and children of missionaries—among them other prominent writers and activists—who came to be among the mid-20th century’s most vocal opponents of white supremacy and imperialism. Their stories show how the missionary movement, which was started to bring Christianity to faraway lands like China, came to have its most profound impact on the culture of the United States.

American Protestants of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were a prosperous, confident lot, convinced that their own religion could save the world’s peoples from degradation. “Go and make disciples of all nations,” Jesus of Nazareth was understood to have directed (Matthew 28:19). Thousands of Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Methodists, and members of other denominations, often graduates of Oberlin, Princeton, and Yale, went all over the globe, but in the highest numbers to China, Japan, and India. They built schools and hospitals as well as churches, and they learned the local languages. Many of their children counted Chinese or Japanese as their native tongue.

Among the influential children of this group of missionaries was Pearl Buck, whose 1931 novel The Good Earth approached the Chinese in much the same concrete, humanizing fashion in which Hersey depicted the Japanese. During World War II, missionary organizations were by far the most visible groups opposing the internment of Japanese Americans. In the U.S. State Department and in intelligence agencies, missionary sons criticized traditional links with the European colonial powers and urged new alliances with non-white, decolonized peoples. Children of missionaries were prominent among the Anglo Americans who devoted energies to the civil rights struggle of black Americans, as early as the 1940s and 1950s. In 1947 a missionary son from the Philippines, George Houser, was with the black activist Bayard Rustin on the first “freedom ride,” which became the model for the more famous interracial defiance of Jim Crow public accommodations in the early 1960s.

A closer look at the career of John Hersey reveals how he took the ethos of his childhood and gave artistic and political expression to the ethical imperative to get “beyond national boundaries,” as he put it, and to embrace “the world as a whole.” Hersey’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of 1944, A Bell for Adano, introduced readers to an American soldier devoted to the interests of a community of war-devastated civilians in occupied Sicily—people who, like the Japanese of Hiroshima, were citizens of what had been an enemy regime. Years later, Hersey allowed that this soldier was a “displaced missionary”—a man determined to bring what justice he could to a wounded world.

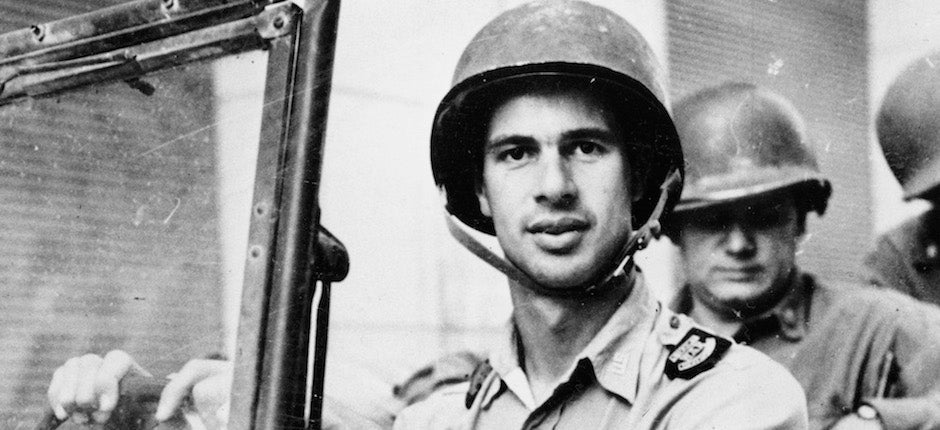

Pearl Buck receiving the Nobel Prize in literature from the King of Sweden in 1938. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hersey described many of his other fictional characters as displaced missionaries, too, including the hero of his 1953 novel, The Wall. There, in what is usually regarded as the first serious fictional treatment of the Holocaust in English, a Jewish scholar records the experience of the Warsaw Ghetto with a sensitivity that Jewish reviewers found astonishing—particularly because it was the imaginative creation of a Skull-and-Bones man from Yale whose parents had been Congregationalist missionaries. Hersey also wrote with widely praised sensitivity about African American victims of racist violence in The Algiers Motel Incident (1968) and about the Japanese Americans confined to prison camps after Pearl Harbor.

Hersey’s finest literary achievement, other than Hiroshima, was about a real missionary, not a moral surrogate for one—and it shows that he eventually grew critical of the missionary endeavor. In 1986, he wrote the epic novel The Call, offering a rueful narrative of the entire missionary project in China. The missionaries won few converts and came across to many Chinese nationalists as agents of Western imperialism. Hersey showed in painful detail that what doomed the missionary project from the start was its arrogant presumption that American Protestants knew better than the indigenous peoples of Asia how to live a good life. Hersey himself retained and redirected the egalitarian, all-men-are-brothers outlook that missionaries espoused, but The Call registers his eventual conclusion that the missionary project violated that very ideal of human solidarity.

This sentiment was common among Hersey’s fellow missionary children. In 1933, Buck declared herself “weary unto death with this incessant preaching,” and demanded that American Protestants switch from conversion to social service as the theme of activities abroad, traumatizing the Presbyterian community she had grown up among. But between the 1930s and the 1950s, most of the ecumenical, “mainline” denominations made exactly this change. The resulting social service programs had an unexpected but important long-term effect: They served as a model for the Peace Corps.

The careers of Hersey, Buck, and many others who shared their missionary upbringing were driven by a recognition that the peoples of the world were much less in need of American Protestant supervision than had been supposed. The missionary encounter with peoples beyond the historically Christian North Atlantic West produced relatively generous dispositions toward the varieties of humankind. The memoirs and letters of missionary families record the spiritual impact of discovering how deep and complex were the civilizations of Asia, and how emotionally vibrant and intellectually capable were many of the rank and file “heathens” the missionaries had come to liberate from a life of darkness. These foreign peoples were not so bad, not so much in need of being made over into copies of Baptists in Indiana or Virginia. Hersey’s The Call ends with the disillusioned missionary protagonist—based largely on Hersey’s own father—trying to assure himself that “it had not been all error.”

Perhaps it was American life that needed to be changed? Many of the folks at “home” had narrow, provincial attitudes that were obstacles to a genuine, world-wide community. Instead of trying to convert the rest of the world, the missionary-influenced Protestant Americans applied to their home society the “Christian” ideals that continued to be affirmed by those who remained committed to the faith, and also, in a secularized fashion, by the many who, like Hersey and Buck, abandoned the churches of their parents. The blowback from missionary experience abroad was profound; it took form as an obligation to transform the society that had generated the missionary project to begin with.

[…] the missionary movement, which was started to bring Christianity to faraway lands like China, came to have its most profound impact on the culture of the United States.

A remarkable feature of this imperative was its moral intensity, inherited from the original missionary endeavor. “In the night, or a dozen times a day,” Buck once told her sister, “I find myself thinking furiously about the peoples of the world, as if they were my personal responsibility.” Indian-born Robert Goheen, who as president of Princeton University orchestrated the admission of women to that previously all-male institution and hired its first black faculty member at the rank of Professor, said that his missionary parents instructed him to “live a life of service.”

Campaigning against white supremacy in multiple contexts, this group of Americans advanced an outlook that would later be called “multicultural.” Indeed, the first appearance of that word in print is found in the 1941 novel Lance, written by a son and grandson of missionaries, Edward Haskell. Although multicultural did not come into common usage until about 1990, several missionary-inspired writers employed it during the intervening decades. In this spirit, missionary children led the development of Asian Studies in American universities and colleges after World War II. Edwin Reischauer, the academic entrepreneur who built Japanese Studies at Harvard University and later served as Ambassador to Japan, was a missionary son. Missionary-dominated programs in “Foreign Area Studies” undermined what later came to be called “Orientalist” images of foreign peoples long before the 1970s, when Edward Said called yet wider public attention to the depth of American prejudice against the cultures of the “the East.”

Not everyone in this cohort shared this perspective. The case of Henry Luce, the influential publisher of Time and Life, can remind us that there were important exceptions to the pattern. Luce was born in China, the son of Presbyterian missionaries. Later, his notorious advocacy of an “American Century” put him at odds with most of his fellow former missionary kids, who faulted Luce as an extreme nationalist and even as an imperialist. When Luce urged Americans of the 1940s to use their power to make the world over in their own image, he transferred the old missionary goal of conversion to the American nation-state. Among Luce’s most severe critics was Hersey himself, who had worked for Time before he angered Luce by publishing Hiroshima as an article for the rival magazine, The New Yorker.

Luce’s boss-the-world outlook has often been assumed to exemplify the American missionary mentality, but Hersey was more genuinely representative. He disagreed with Luce about almost everything, but is rarely associated with the missionary past. Luce, the vigorous nationalist, learned little from the blind spots of the missionary project that nurtured him. But Hersey flew in the missionary dusk with the wings of Minerva.

David A. Hollinger is Professor of History Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. His previous books include After Cloven Tongues of Fire (Princeton, 2013). This essay is based on his new book, Protestants Abroad: How Missionaries tried to Change the World but Changed America

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary Editor: Eryn Brown.

Add a Comment